Preamble

This article was 2 years in the making. Ever since writing the post about diagnosing ADHD in 2021, I’ve been meaning to write one about something closer to my heart – diagnosing autism spectrum condition (ASC). However, many things got in the way, namely emotional barriers and procrastination (this is my 2-year procrastination as a neurotypical). The former was mainly due to how difficult it was to write an article like this. The field of adult ASC diagnostics is still pretty much in its infancy. Research and literature are all over the place (present-tense as it still is). The field is still trying to find its own footing and grounding. How then do I synthesize something as complex and nuanced into an article? That was my biggest emotional hurdle – a fear that I would misinform, and perhaps be wrong about it myself. The fact that you are now reading this article would therefore suggest that both [1] emotional barriers; and [2] procrastination had been resolved. Or perhaps it was just foolhardiness on my part. Nonetheless, I hope to express my opinion as a clinician involved in the diagnostic process in this article.

Tl;dr

- Having a diagnosis of ASC can be validating and important

- Diagnosing ASC in adults is a challenging process, termed “the 4 problems”

- ASC evaluation should be done by clinicians who have the relevant expertise, training, and competence

- Good comprehensive evaluation should include multiple data points (self-, informant-, clinician observation), and possibly a consensus-based diagnosis

- Not receiving a diagnosis doesn’t invalidate your difficulties or experiences

- We should move away from categorical approaches towards conceptualising our identity dimensionally

Diagnosis and identity

Picture this: You are 30. You’ve got a master’s degree in engineering. You’re employed in this firm and had been for the last 6 years. Financially, you’re independent. No major loans or commitments. By most measures, you’re decently well to do. Educated, employed, financially stable. What more can a 30-year-old ask for? But something’s amiss. Day by day, you repeat the same routine. Wake up, work, go home. Friends? What are those anyway? Colleagues at work? Cordial, nothing more. Or perhaps the occasional hinderance to your projects. Work lunches? You eat alone. Talking is way too difficult. Being in a group is way too difficult. You struggle to know where and who to look at. Upon reflection, you’ve realised that it had been this way all along. When you were in preschool. When you were in school. When you were in college and in university. Why was it so hard? Why do you not know what and when and how to say and speak and interact? One day, someone suggested that you get seen professionally. You do, because ‘why not?’ you think. You get seen by the specialist and evaluated. They tell you that you’ve got ‘Autism’. They explain what autism is. Suddenly it all made sense. The 30 years of living life as someone standing on the outside of the circle, but never in. Suddenly you realise why it had always been difficult for you. Suddenly, you feel… liberated. Vindicated.

The above is a fictional depiction to illustrate how a diagnosis can have a powerful emotional and psychological impact on people (individuals, relatives, friends, partner). It is validating (Finch et al, 2022). It also provides access to much needed care and support services (Huang et al., 2022). Given the impact of a diagnosis, it is no wonder that many people try to get evaluated, or resort to self-diagnosing (Overton et al., 2023). It is important to them after all.

With the wealth of information at our fingertips, a quick Google search using the words ‘autism’, ‘diagnosis’, ‘criteria’, would easily net you the diagnostic criteria on either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Scrolling through the criteria, you could quickly identify with the items on the list. Check, check, check. You’ve met the criteria. “I am autistic”, you think. I have lost count of the number of times a client of mine had brought that up. The number of enquiries seem to increase significantly in April each year, during Autism Awareness Month, when social media blossom with posts and guides and “quick tests” to determine if someone is autistic.

At the clinic, I take my time to gently explain and share with each client what my professional opinion was. Sometimes they do seem to fit the profile. Other times not so. For the former, I explain the evaluation process, the costs involved, and the clinical and practical (social, psychological, emotional, insurance) implications of having a diagnosis. They then decide how they would like to proceed. For the latter however, sometimes they disagree. They have every right to. They cite unheard-of-tests from the internet to justify their beliefs. They tell me that some other therapist or community worker or counsellor had told them that they were autistic.

Diagnosing ASC in adults

Diagnosing autism in adults is unfortunately not a straightforward process as some seem to believe. By ‘some’, I am referring to both laypersons and clinicians alike. It is in fact an extremely nuanced process, beyond not simply looking to superficially meet the diagnostic criteria on either the DSM or the ICD. It is not a coincidence that the NICE guidelines specifically recommended that “A comprehensive assessment should be undertaken by professionals who are trained and competent” as the first statement of guideline 1.2.5 on diagnosing autism in adults.

While it might not come as a surprise that self-diagnosis might be inaccurate, non-specialist clinicians are also very prone to misidentifying (false positives or false negatives) autism. It had been found that up to a quarter of community ASC diagnoses made were not supported when evaluated by a specialist team (Hausman-Kedem et al., 2018). Those were potentially false positives. Another study conducted in Australia found that in only 33.3% of the cases evaluated was there strong interrater agreement between diagnosing clinicians (Taylor et al., 2017). Another study conducted by a peer of mine found that only 22% of general mental health clinicians considered ASC as a possible diagnosis when tasked to evaluate vignettes for potential diagnoses (Leong et al., 2019). So what exactly makes diagnosing autism in adults so challenging?

I would like to draw your attention to what I think are “the 4 problems” of adult autism evaluation.

The conceptualisation problem

A diagnosis is fundamentally a system of classification. As such, the conventional challenges associated with categorising or classifying things apply. For example, how do we conceptualise and classify if a species is a mammal? The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines a mammal as “any animal that gives birth to live young, not eggs, and feeds its young on milk.” How then should we classify a platypus? It lays eggs. Some might argue for the platypus to be excluded from the mammalian classification. Others, try to redefine the classification to be inclusive of the platypus. Such is the fundamental challenge of systems of classification.

In medical classification, conditions or diseases are sometimes classified by etiology (causes). In others cases, such as with the DSM, the classification is done by identifying co-occurring clusters of symptoms – or syndromes/disorders. The latter system has its flaws, and the elephant in the room that needs to be addressed are the problems that have plagued the DSM (and ICD) since their conception – vagueness and validity (Ghaemi, 2018). To the untrained person, ASC is “clear”. It is “clearly defined” in the DSM. But what then exactly is autism? How do we theoretically and clinically define autism? How can we confidently determine who is ASC and who is non-ASC in the absence of objective markers? One might be tempted to provide the common textbook answer, that autism is “a neurodevelopmental condition defined by persistent difficulties across multiple contexts within two distinct domains: [1] social communication and interaction and [2] restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or interests”. But what then defines difficulties in social communication and interaction? How do we measure them? What is the threshold? What about restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour? What constitutes that? How repetitive do they have to be?

Until we have a way to systematically align and answer the questions above, the vagueness of the DSM and ICD would continue to plague us and cause debates and disagreements between clinicians and researchers alike. In fact, some of the liveliest debates occurred in the years leading up to the release of the DSM-5 (fifth edition of the DSM) in 2013. With the release of the DSM-5, some of the previously distinct categories such as ‘Autistic Disorder’, ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’, and the vague ‘Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified’ have been merged under the new ‘Autism Spectrum’ umbrella. Some have lauded the move as heralding progress in the field of neurodiversity. Others lamented the loss of their distinct identity. Some individuals have found themselves lost – for while they were once diagnosed, they have now lost their diagnosis under the revised ASC system of classification. Given how important a diagnosis could be in relation to one’s identity, what then should we make of those who have lost their diagnosis due to such revisions?

The diagnosing problem

Given the vagueness of the DSM and ICD and how autism was conceptualised, it is no wonder that clinicians on the ground dispute and argue over how to best identify or diagnose ASC. Historically, autism was a “children’s problem”. It was noticed and identified predominantly amongst children. In fact, early conceptualisation termed autism “childhood schizophrenia”, which was theorised to be caused by “refrigerator mothers” (note: that theory has been thoroughly debunked). Since its wobbly beginnings, copious amounts of research involving the sweat and blood of many clinician-scientists in the latter 1900s have led to the creation of many tools hoping to answer that question of identifying ASC in children. Without waxing lyrical, there are currently dozens upon dozens of tools and questionnaires that have been developed and validated in an attempt to best identify autism in children. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS, now in its second edition) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R) emerged as the forerunner and “gold standard” in the process.

It was not until the 2000s that an interest in autism in adulthood started taking shape in academia. Afterall, many of these children grow up into adults. What then? How do we support them? Could there possibly be adults who were autistic but were not identified earlier? How do we identify them? Do we have the right tools to identify them? This presented as a wholly different set of challenges to autism researchers worldwide than before. New tools were developed (e.g. RAADS-R). Older tools were also repurposed for the new task at hand (e.g. ADOS-2 module 4, Adult Autism Assessment). However, the fundamental problem still existed. What is ASC? How does it look like in adults who were not identified in childhood? Why were they not identified in childhood?

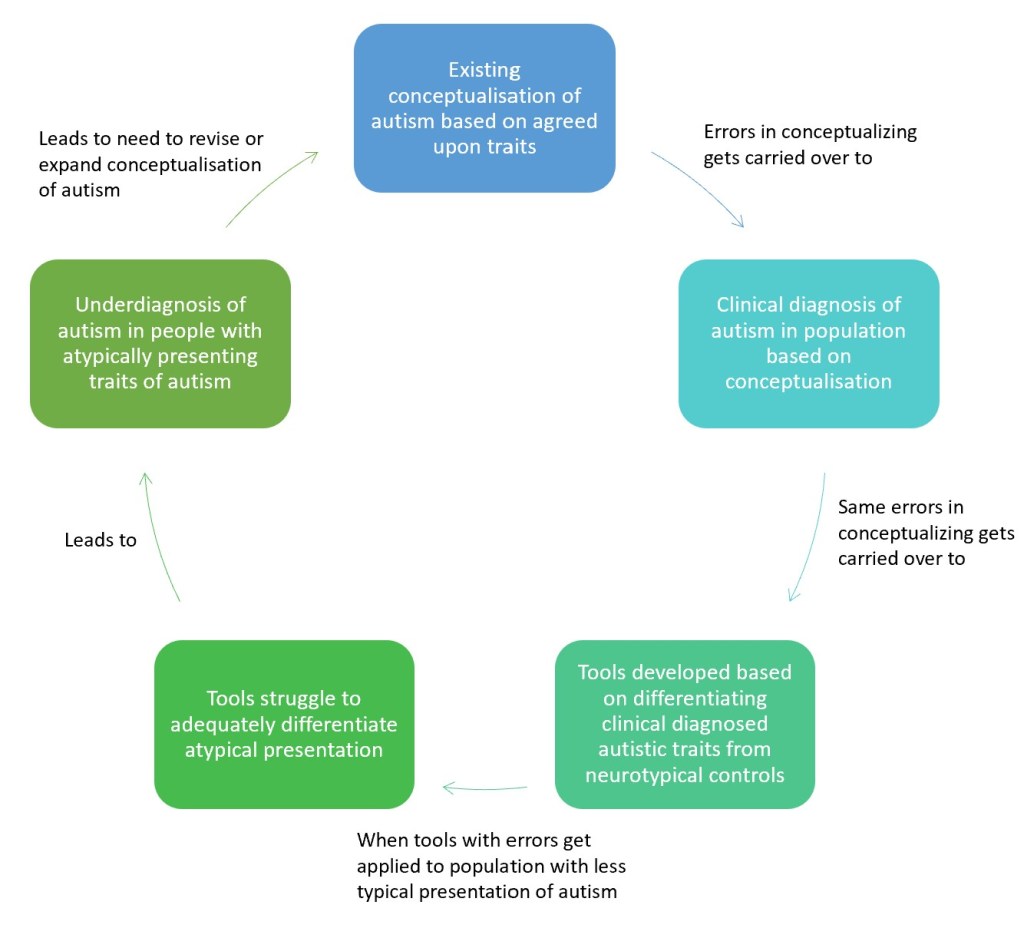

The diagnosing problem can therefore be understood to be consequent to the conceptualisation problem. Existing tools (such as the ADOS or the ADI-R) were developed and validated against a clinically identified and vaguely conceptualised autistic population versus a neurotypical control group. Once validated, these tools were then used to identify future cases of autism among the population. As such, errors and challenges associated with the initial clinical conceptualisation inevitably get passed on. That is why it is common for the diagnostic accuracy of existing tools to vary when implemented and studied in different populations. In some cases, replication studies fail to even find any meaningful use for an existing and validated tool. The diagnosing problem could perhaps be understood in the diagram below:

It is precisely because of the cycle illustrated above that we have researchers arguing that many existing instruments used to diagnose autism are male-biased (Navarro-Pardo et al., 2021), because the original conceptualisation of autism is male-centric (that is to say it was conceptually based predominantly on the male presentation of autism instead of the now more widely understood female profile).

The clinician problem

Vague as it may be, the purpose of a diagnosis or label is to help standardise a way of measuring a construct. By sticking to the DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria, clinicians worldwide had something to fall back on in attempting to identify neurodivergence from neurotypicality. But despite the common diagnostic criteria, why is it that the clinical reliability between clinicians when diagnosing autism in adulthood is so poor?

One reason could be that many clinicians are just not competent enough to make those diagnoses. Remember the NICE guideline recommending comprehensive evaluation by professionals who are “trained and competent”? It specifically mentioned “trained” and “competent” because they are two distinct constructs. Being trained doesn’t necessarily makes one competent. All too often I hear colleagues of mine (I use the term ‘colleagues’ loosely to refer to fellow professionals) say that they are ASC diagnosticians because they have been formally trained and certified to administer the ADOS and ADI-R tools. Yes they’re trained, but are they competent? Research has consistently demonstrated that clinician overconfidence leads to diagnostic errors (Cassam, 2017; Berner & Graber, 2008). The ADOS and ADI-R are but one (or two) component(s) of an extremely comprehensive evaluation. In fact, both the ADOS (Adamou et al., 2021) and the ADI-R (Kamp-Becker et al., 2021) have fared quite poorly in the evaluation of autism in adults. In one study, the ADOS resulted in a high rate of false positives among individuals with other serious mental health conditions such as psychosis (Maddox et al., 2017). As such, a clinician trained in those tools and solely relying on them to make clinical diagnoses will risk having high false positives. This risk was also noted by Kamp-Becker and colleagues (2021) when they argued that “Diagnosing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) requires extensive clinical expertise and training as well as a focus on differential diagnoses. The diagnostic process is particularly complex given symptom overlap with other mental disorders and high rates of co-occurring physical and mental health concerns.“

So what exactly makes for a competent clinician beyond the ability to skillfully administer an instrument well? According to Kamp-Becker, it also involves [1] extensive clinical expertise; and [2] a focus on differential diagnoses.

In my opinion, extensive clinical expertise would include having worked extensively with the population that you’re trying to identify and diagnose. In this case, it would be to have significant experience working with autistic adults. Let me illustrate this notion using a task below:

Task: Identify the orange from the grapefruit.

Some of you might get it right and there’s a 50-50 chance that you would, but unless you are an expert or have had extensive experience working with citrus, chances are the task would be difficult for you (I’ve renamed both images ‘orange 1’ and ‘orange 2’ in case some of you think of looking at the names of the source images to help with identifying).

The same goes with identifying autism in adults. How does one hope to accurately identify a condition that they have had limited exposure to and experience with?

It is currently quite well established in research literature that autism in adulthood presents differently than in children. Two key reasons stand out to explain that differential presentation. The first could be attributed to “masking” or “camouflaging” (Alaghband-rad et al., 2023). Generally speaking, adults with autism who were undiagnosed in childhood had better compensatory social skills, in part because of better cognitive abilities, and they possibly also exhibited less externalizing behaviours. You could think of them as the children who flew under the radar when they were younger because they had less behavioural challenges. However, these compensatory strategies may be inadequate to mask underlying traits of autism when demands exceed one’s ability to cope, such as in adulthood, or later in life. Another factor lies in an emerging but less understood “female autism profile” (Green et al., 2019). Many females who receive late diagnoses are misdiagnosed with other conditions such as Borderline Personality Disorder precisely because the female profile is not well understood, given that the traditional definition of autism has been male-centric. Coupled with the issue that many of the tools that were developed to identify autism possibly have a bias towards the male-profile (Navarro-Pardo et al., 2021), and that there are limited sufficiently validated tools in diagnosing autism in adults (Conner et al., 2019), it is no wonder that general clinicians have poorer reliability compared to the experts.

Beyond extensive clinical expertise, Kamp-Becker also made the case for being familiar with differential diagnoses. What is differential diagnosing? It is the capacity to skillfully consider potential alternatives that may masquerade as autism. Let us try another activity out. Read the vignette below and tell me if you think the individual (gender neutral) has autism.

“X was a 24-year-old who struggled with social interactions. They reported longstanding difficulties with friendship. Since primary (or elementary) school, X reported difficulties making friends. They also struggled with making eye contact. Group-based activities were the most difficult. When going to public spaces, X reported that crowds often made them feel overwhelmed, so much so that they could only feel at ease in a quieter location free from people. Apart from social difficulties, X also reported difficulties with changes. They have highly structured routines and reported needing to strictly stick to those routines. Failure to do so often resulted in anger and intense anxiety.“

Do you think X has autism?

The truth was that I conceptualised X’s vignette to be the profile of someone who has both Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD).

Some traits from SAD (taken from the DSM-5) that may mimic behaviours associated with autism

- Marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others. Examples include social interactions

- In children, the anxiety must occur in peer settings

- In children, the fear or anxiety may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, clinging, shrinking, or failing to speak in social situations

- The social situations are avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety

Some traits from OCPD (taken from the DSM-5) that may mimic behaviours associated with autism

- Is preoccupied with details, rules, lists, order, organization, or schedules to the extent that the major point of the activity is lost

- Shows perfectionism that interferes with task completion

- Is overconscientious, scrupulous, and inflexible about matters of morality, ethics, or values

- Is unable to discard worn-out or worthless objects even when they have no sentimental value

- Shows rigidity and stubbornness

As autism is after all a diagnosis that is established by evaluating observed or reported behaviours, it is therefore essential that any evaluating clinician be skilled in differential diagnosing to distinguish between ASC and other possible conditions (Ashwood et al., 2016).

Expertise, training, and differential diagnosing aside, even the most skilled clinicians are not spared the effects of confirmation or other cognitive biases (Satya-Murti & Lockheart, 2015). Caution is advised when evaluating autism in adults. Another way to balance out the effects mentioned in “the clinician problem” might perhaps lie in the concept of strength in numbers. In this context, that might be arriving at a diagnosis based on expert consensus than an individual’s professional opinion.

The reporter problem

The final challenge in diagnosing autism in adults would be what I term “the reporter problem”. As psychiatric diagnoses rely quite significantly on self- or informant-reports, the quality of the reports often determines the conclusiveness of the diagnosis or evaluation. One potential challenge with the reliance on self-report would be the possibility of over- or underreporting depending on the cognitive biases of the reporter (Merten et al., 2020). For example, individuals who strongly believe that they have autism may overreport symptoms, or interpret some of their experiences to be representative of autistic traits when in fact they could potentially be due to other conditions such as social anxiety or OCPD (as illustrated above). In fact, Frith (2014) shared that “there are individuals with problems in social relationships and other features that are reminiscent of autism, who have either claimed or been given the label Asperger syndrome, but actually belong to a different category. Sadly, this category is as yet undefined and may even be part of neurotypical individual variation.” Ashwood and colleagues (2016) also found that self-report scores on a known ASC diagnostic tool failed to predict eventual diagnosis, suggesting that while self-reports were important in the diagnostic process, they were insufficient.

The second reporter problem would be that of an informant report. As autism is conceptualised as a neurodevelopmental condition, it theoretically would imply that the autistic brain is one that had developed differently from the typical brain (hence the term ‘neurodivergent’). As such, one important aspect of evaluating for developmental conditions would be the person’s developmental history – their achievement of specific milestones, or their early childhood behaviour that may suggest autistic traits before the emergence of compensatory or masking strategies. In fact, the diagnostic criteria for both ASC and ADHD (both neurodevelopmental conditions) necessitates that symptoms were present in childhood. The challenge with obtaining developmental history for adult evaluation lies in the clarity or reliability of their parents’ or informant’s recollection of a distant past. Parents or informants often struggle to provide reliable or detailed recounts of an adult’s childhood history, making the diagnostic evaluation particularly challenging from a developmental perspective. In the absence of reliable childhood history, how should we know if the current difficulties emerged from a divergent brain and did not begin when the person was 13 years old from a traumatic brain injury?

Evaluating autism in adults

Thus far I hope that I have given you a snippet of the nuances and challenges of diagnosing autism in adulthood. Given these challenges, how then should a comprehensive evaluation of ASC in adulthood look?

Personally, I’m of the opinion that any formal diagnostic evaluation should:

- Be conducted by a specialist clinician with the relevant expertise;

- Involve the three components of information gathering: self-report from a validated adult ASC scale (e.g. the RAADS-R), informant-report to obtain information on current behaviours and early developmental history, and a clinician observation scale (e.g. the ADOS-2 module 4);

- Include a structured clinical interview (e.g. the Royal College of Psychiatrist Interview or ADI-R) of both client and informant;

- Include scales or interview items which also evaluate for co-morbid or differential diagnoses; and

- Involve a multi-member team of experts for consensus diagnosis (to reduce confirmatory/cognitive biases of the primary clinician).

Other useful adjunctive assessments include an IQ or cognitive test, and evaluating adaptive function, strengths, and needs in order to generate a holistic profile of the individual that will guide treatment or intervention (The NICE guidelines recommend something similar).

Traits vs threshold

It is precisely because of the benefits a diagnosis may confer to individuals seeking to explain their lifelong difficulties that people sometimes get upset or feel invalidated when formal and comprehensive evaluation results in a null (no ASC). As a duty of care to my clients, I often start my evaluation by asking why the individual is seeking evaluation, as well as setting expectations that not everyone who presents with traits would meet the diagnostic threshold to receive a formal diagnosis. I would also share that the threshold is arbitrary (see “the conceptualisation problem” above), based on the current consensus and as operationalised in the DSM. Failure to meet full criteria does not negate the presence of autistic traits and the associated difficulties. The individual’s experiences are still valid and relevant, and care and intervention could still be offered despite not meeting the threshold for a formal diagnosis.

To illustrate the concept, I sometimes use the exam analogy: “Consider the grading system on an examination. A 75/100 mark might give you an ‘A’ grade. Anything below 75/100 would therefore be understood as ‘not A’ grade (it could be ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’ etc.). Someone with a score of 74 would thus be classified as ‘not A’, while someone with a score of 75 would be classified as ‘A’. In terms of content knowledge and understanding of the subject, would we say that 74 and 75 are qualitatively that different? Perhaps not. But nonetheless, they were differentially classified because of the arbitrary threshold of 75. One might argue that it is unfair, and perhaps it is. Some might suggest that we adjust the cutoff to 74/100 in classifying ‘A’ from ‘not A’. Sure we could. But if we do, what about those scoring 73 who now just narrowly miss the cutoff by 1-point? Is it not unfair for them? Should we then adjust the threshold to now be 73/100? What about 72 then? And 71?“

The process of categorising would inevitably bring about some complications and unfairness, especially when things in reality exist on a continuum than they do in clearly distinct silos. Should a platypus be a mammal or not? What about a whale? What about the criteria of mammals needing to give birth to live animals? Or mammals needing to have hair on their skin?

In the context of the DSM, I personally believe that we need to move away from seeing things as strictly categorical (receiving an ASC diagnosis = challenges are valid; not receiving an ASC diagnosis = difficulties are “made up” or “in your mind”), towards a dimensional approach (some have more challenges, others have less). I recognise that practical implications exists, and some people can only qualify for insurance or services if and when they receive a categorical psychiatric diagnosis. In the area of identity formation however, perhaps that shift might do us more good. It is only in doing so, may we then conceptualise ourselves not based on psychiatric labels, but more holistically as unique individuals each with our own needs and strengths, each trying to waddle our way through life in unique circumstances and contexts.

Concluding remarks

Assessing ASC in adults is an extremely tricky process. Multiple challenges complicate the process despite the seemingly straightforward DSM/ICD criteria. Among these are “the 4 problems”: conceptualisation, diagnosing, clinician, and reporter problems, any of which could throw a wrench in the wheel. Nonetheless, having a formal evaluation could bring about important emotional, psychological, and practical benefits to individuals who have long struggled with an underlying “difference”. If you are considering seeking formal evaluation, do ensure that your clinician ideally has, as Kemp-Becker puts it, “extensive clinical expertise and training as well as a focus on differential diagnoses.”

Eugene

Eugene is a clinical psychologist with nearly a decade’s worth of experience working with and in specialist autism services involved in diagnosis and intervention. He has had experience working with the neurodivergent community across the lifespan, from toddlers to middle-age adults. The views here represent his opinion made in his personal capacity, and should not be taken to be professional advice.

One thought on “Opinion/Commentary: Diagnosing Autism in Adults – A Clinician’s Perspective”